Mr Speaker, Sir,

Of all the free trade agreements that we have signed with other countries, the Singapore-India Comprehensive Economic Cooperation Agreement, or CECA, has attracted the most attention for two reasons.

Firstly, it contains a clause in Article 9.5 granting entry to persons in 127 professions, which is not found in the other free trade agreements that Singapore signs with other countries.

Secondly, there was a rapid increase in the number of Employment Pass holders from India working in Singapore in the past 15 years. Minister for Manpower has revealed that the proportion of EP holders from India has increased from one in 7 in 2005 to a quarter in 2020. Based on 65,000 EP holders in 2005 and 177,000 EP holders in 2020, we can calculate that the number of EP holders from India increased by 377% from 2005 to 2020, an average growth rate of 11% per year. In comparison, the proportion of EP holders from China has remained stable, therefore implying that the number of EP holders from China grew in tandem with the increase in the total number of EP holders, i.e. an increase of 172% from 2005 to 2020, or an average growth rate of 7% per year.

The Minister explained that the increase in migrant workers from India is a global trend. Based on the figures provided in the Ministerial Statement, the number of international migrants from India increased from 10 million in 2000 to 18 million in 2020, or an average growth rate of 3% per year. If we assume a stable growth rate, then for comparison purposes, the global growth of migrants from India over the period 2005 to 2020 would be 55%. The growth of 377% in Singapore far outstrips the global trend. To summarise, the percentage growth of EP holders from India to Singapore is nearly 7 times that of the global trend. What then is the basis for claiming that the growth rate in Singapore is a reflection of global trend? Can the Minister provide examples of other countries that experienced similar growth to Singapore’s?

Singaporeans who experienced such changes in their daily lives naturally searched for reasons, thus putting CECA in the spotlight, for it seems to offer an explanation.

The Ministers have explained that the clauses on manpower are still subject to our manpower policies, and also pointed out that Japan and South Korea have similar agreements with India.

Japan and South Korea have natural barriers in the form of language, thereby making them less accessible as compared to Singapore. Other English-speaking countries are presumably more cautious about signing such an agreement.

We are all familiar with the effect of messaging in a commercial context. 2 identical products, one with a good advertisement campaign with a strong message and another with a weak message can have very different sales outcomes. The same applies to other areas of life as well. A strong message is a powerful tool.

This clause on movement of professionals, in an agreement signed by the governments of 2 countries, sends a strong message of welcome to Indian professionals. To ignore this effect and conclude that the presence or absence of this clause does not change anything since it is still subject to our manpower policies and criteria is being blinded to reality by technicalities.

Now consider 2 different countries, one with whom we signed an agreement on the movement of labour and another without. The agreement imposes an obligation to grant work permissions to nationals from the first country, provided our manpower policy requirements are met, but no such obligations exist with respect to nationals from the latter country. So the agreement forms the first gate, and our manpower policies form the second gate.

So to address the concerns of Singaporeans, we need to go beyond CECA to our foreign manpower policies in general.

Jobs Policy

Currently, quotas are imposed on work permits and S Passes. There are no quota for Employment Passes which are for jobs with a minimum salary of 4,500 dollars and in the case of the finance industry, 5,000 dollars.

Now if we impose only a minimum salary requirement and open up all jobs beyond that salary to fair competition globally, then when our small population compete fairly with the huge global population for those jobs, mathematically speaking, we can expect a significant proportion of the jobs to go to foreigners. As the world becomes more integrated, it will only get more so. So while fair competition sounds ideal, it is neither tenable nor practical. This is especially so when many other developed countries impose a tighter level of control on foreign manpower, making it an unlevel playing field for Singaporeans competing for jobs globally. It is our view that tighter controls on foreign manpower are necessary.

The government maintained that by opening up to global labour supply, we bring in more jobs for Singaporeans, and that the foreign workforce provide a buffer for job losses for locals in times of economic downturn, as in the recent pandemic.

The Minister has said that local PME jobs have increased by 380,000. My colleague Mr Leong has raised doubts over claims that our foreign manpower policies have created more jobs for locals and queried this number. Allow me to elaborate. A portion of the 380,000 jobs could be due to reclassification, a result of PRs becoming citizens, and foreigners become PRs.

For example, suppose 1,000 foreigners holding PME jobs applied for and became PRs. Then these 1,000 jobs previously classified as foreign PME jobs, became local PME jobs when they became PR. There is no increase in jobs, but there is an increase of 1,000 in local PME jobs and a decrease of 1,000 foreign PME jobs.

Each year, we have about 20,000 new citizens on average. Over 15 years, that’s an increase of about 300,000. The number of PRs has been stable in recent years. So the total number of residents, comprising both citizens and PRs have increased by about 300,000. While not all the 300,000 increase in citizens and PRs are holding PME jobs, it still suggest that a significant portion of the 380,000 increase in local PME jobs could have come from change in status of the job holders, not due to creation of new jobs. Can MOM clarify whether the changes arising from the change in status of the job holder is included in the 380,000? If so, how many new local PME jobs were created, netting off the effect of reclassification?

As for the point on foreign labour providing a buffer for job losses in an economic downturn, our foreign workforce is large enough that even if we were to cut the foreign workforce significantly, the same buffer would still exist.

In addition, what is not addressed is underemployment, an area my colleague Mr Leong has spoken on earlier. Singaporeans who were displaced from their jobs may subsequently find employment that do not commensurate with their qualifications, skills or experience. Given that this concern has been raised for many years, have we made any attempts to measure underemployment? Does the labour survey contain questions to identify and measure underemployment, apart from hours of work? If not, why not? If so, can MOM share the information on the extent and trend of underemployment in Singapore in the last twenty years?

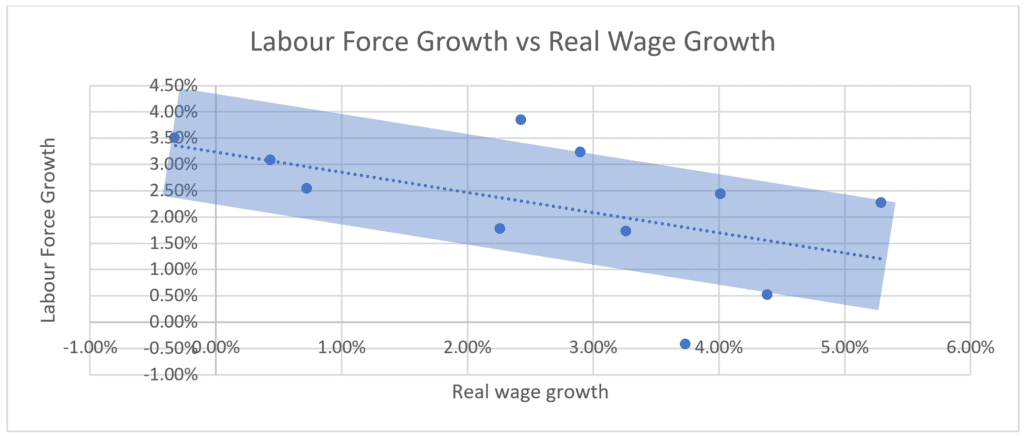

With your permission, Mr Speaker, may I ask the Clerks to distribute a handout on a comparison of our labour force growth versus median wage growth?

| Labour force growth | Median wage growth (real) | |

| 2009 | 3.06% | 0.44% |

| 2010 | 3.50% | -0.32% |

| 2011 | 3.23% | 2.90% |

| 2012 | 3.85% | 2.42% |

| 2013 | 2.44% | 4.01% |

| 2014 | 2.53% | 0.72% |

| 2015 | 2.26% | 5.30% |

| 2016 | 1.72% | 3.26% |

| 2017 | -0.43% | 3.74% |

| 2018 | 0.51% | 4.39% |

| 2019 | 1.77% | 2.26% |

Economic theory tells us that when supply of labour increases, all else being equal, the price of labour, or wages in other words, decreases. There are of course other factors affecting wages, with the supply of labour being one factor. But looking at the labour force growth and the real wage growth from 2009 to 2019, we see that in years of higher labour force growth, we tend to have lower real wage growth and vice-versa, when labour force growth is lower, real wage growth is higher.

The handout contains a scatter diagram showing the correlation and the regression line between labour force growth in Singapore and the real wage growth. The regression line is negatively sloped, which means that these 2 move in opposite directions. In other words, when labour supply growth goes up, real wage growth goes down.

As we pursue economic growth, we should always bear in mind that economic growth is a means, not an end. A means to improve the lives of Singaporeans. Increasing labour supply by bringing in migrant workers increases economic growth but dampens local wages – a trend we observed in our study using statistics from 2009 and 2019. We would like to ask the Minister for Manpower whether the Ministry has studied the effects of how labour force growth depresses real wage growth, and if so, what is their conclusion.

If our priority is economic growth, then indeed we should welcome all foreign direct investments (FDI) even if they should require a huge influx of foreign manpower.

But if our priority is wage growth, then we would be more selective and focussed in bringing in FDI that benefit primarily local workforce and does not require a high proportion of foreign manpower. Trading economic growth for wage growth is a worthwhile exchange.

The government had previously indicated that it is aiming to limit the proportion of foreign manpower in our labour force to one-third. Is that still the target this Government is holding to? With this target in mind, does the Government turn down FDIs that would require a higher proportion of foreigners? How is this target put into effect?

My colleague Mun Wai has spoken extensively on manpower policies and proposals. I will now touch on another area of concern, and that is enforcement.

Strengthening Enforcement

There’s a Chinese saying: 上有政策下有对策

Which, translated, means that while the government have policies, those who are governed have ways to deal with it or counter measures.

There have been several widely publicised cases of underpayment by employers. This is when the employers make inflated claims of staff salaries to MOM or staff are paid full salaries but told to return a portion to the company in cash. This practice effectively circumvents minimum salary requirements for S pass and EPs.

The reality is that this practice has been going on for years. Mainly because money is returned in cash, it’s difficult to trace unless a thorough investigation is conducted or the employee reports the matter to MOM.

Recent calls by a Labour MP and a TAFEP member asking for greater teeth to be given to TAFEP for enforcement is also an indication that current level of enforcement is not meeting our needs.

Recently a business executive who is tendering for various projects, highlighted to me that this practice has created an uneven playing field. He is aggrieved that while he does the right thing to employ Singaporeans wherever possible and to report to authorities actual salaries paid, his competitors would use such tactics to lower their costs and therefore offer much lower prices to win tenders, with salary being huge proportion of the cost for projects.

Organisations calling for tenders do not have incentives nor reasons to care whether or not such practices are going on in the company winning the tender. While we are trying to build a Singaporean core in companies, should we not strengthen our policing of such practices? It would be ironic if companies that break the rules are rewarded over law abiding ones.

The increasingly common practice of subcontracting can also dilute the effectiveness of enforcement. Separate companies can be set up to take over certain business functions and “take the fall” should they be discovered to have violated any manpower policies and regulations.

There are also various other ways of circumventing the rules, for example, the use of phantom employees to meet quota requirements. We would therefore like to suggest two ways of strengthening enforcement.

Firstly, we propose that for large contracts or tenders, a certain level of duty of care be imposed on the purchasing company, for example, to include audit requirements on successful tenderers to ensure compliance with manpower policies. This will provide incentives for companies to comply and also make evasion via subcontracting more difficult.

Secondly, we suggest the govt explore the licensing of Human Resource Managers. Currently we license certain professions for example doctors, lawyers, and real estate agents. We impose on them certain standards of service and code of conduct. Those who fail the standards can have their license taken away. We can similarly license HRMs and task them to ensure compliance with manpower policies in their companies. Large employers should be required to hire licensed human resource managers, who will have personal responsibilities to ensure full compliance with government manpower regulations and those who do not risk penalties which can include losing their license. A high turnover of HRMs will also be a tell-tale sign of trouble.

In Conclusion

We agree that maintaining an open economy and taking in manpower from other countries is beneficial. The issue is one of degree. To what extend do we take in foreign manpower? At what point does it become an overdose? We are not asking for a closed economy or closed labour market, but a reduction in our reliance on foreign manpower to a lower level and keeping a close eye on wage growth while we adjust the level of foreign participation in our labour force.

It would also be a good time to reiterate that Ministerial salaries should be pegged to median wage. Increasing labour supply leads to GDP growth, which increases ministerial salaries. However the same labour supply increase depresses median wage growth.

Our current model can lead to a divergence in the movement of the salaries of political leaders and those of average Singaporeans. This is not a good basis on which to build trust. On the other hand, if Ministerial salaries are pegged to

median wage, it sends convincingly the message that the political leaders and Singaporeans at large are on the same boat, more so than any words can.

Today, representatives from various parties talk about the importance of a Singaporean core. Let us not stop at lip service. As the saying goes, what gets measured gets done. Make it concrete. Make the percentage of Singaporean workers into a government KPI.

Thank you.